4. Policy Iteration

In this lecture we

- formally define policy iteration and

- show that with $\tilde O( \textrm{poly}(\mathrm{S},\mathrm{A}, \frac{1}{1-\gamma}))$ elementary arithmetic operations, it produces an optimal policy

This latter bound is to be contrasted with what we found out about the runtime of value-iteration in the previous lecture. In particular, value-iteration’s runtime bound that we discovered previously grew linearly with $\log(1/\delta))$ where $\delta$ was the targeted suboptimality level. This may appear as a big difference in the limit of $\delta\to 0$. Is this difference real? Is value-iteration truly inferior to policy-iteration? We will discuss these at the end of the lecture.

Policy Iteration

Policy iteration starts with an arbitrary deterministic (memoryless) policy \(\pi_0\). Then, in step $k=0,1,2,\dots$, the following computations are done:

- calculate \(v^{\pi_k}\), and

- obtain \(\pi_{k+1}\), another deterministic memoryless policy, by “greedifying” w.r.t. \(v^{\pi_k}\).

How do we calculate $v^{\pi_k}$? Recall that $v^{\pi}$, for an arbitrary memoryless policy $\pi$, is the fixed-point of the operator $T_\pi$: $v^\pi = T_\pi v^\pi$. Also, recall that $T_\pi v = r_\pi + \gamma P_\pi v$ for any $v\in \mathbb{R}^{\mathcal{S}}$. Thus, $v^\pi = T_\pi v^\pi$ is just a linear equation in $v^\pi$, which we can solve explicitly. In the context of policy iteration from this we get

\[\begin{align} v^{\pi_k} = (I - \gamma P_{\pi_k})^{-1} r_{\pi_k}\,. \label{eq:vpiinv} \end{align}\]The careful reader will think of why the inverse of the matrix $I-\gamma P_{\pi_k}$ exist. There are many tools we have at this stage to argue that the above is well-defined. One approach is to note that $(I-A)^{-1} = \sum_{i\ge 0} A^i$ holds whenever all eigenvalues of the square matrix $A$ lie strictly within the unit circle on the complex plain (see homework 0). This is known as the von Neumann series expansion of $I-A$, but these big words just hide that at the heart of this is the elementary geometric series formula, $1/(1-x) = \sum_{i\ge 0} x^i$, which holds for all $|x|<1$, as we have all learned in high school.

Based on Eq. \(\eqref{eq:vpiinv}\) we see that \(v^{\pi_k}\) can be obtained with at most \(O( \mathrm{S}^3 )\) (and in fact with at most \(O( \mathrm{S}^{2.373\dots})\) ) arithmetic and logic operations. In particular, the cost of computing $r_{\pi_k}$ is $O(\mathrm{S})$ (since $\pi_k$ is deterministic), the cost of computing $P_{\pi_k}$, with the table representation of the MDP and “random access” to the tables, is $O(\mathrm{S}^2)$. Note that all these are independent of the number of actions.

Computationally, the “greedification step” above just means to compute for each state $s\in \mathcal{S}$ an action that maximizes the one-step Bellman lookahead values w.r.t. $v^{\pi_k}$. Writing this out, we see that we need to solve the maximization problem

\[\max_{a\in \mathcal{A}} r_a(s) + \gamma \langle P_a(s),v^{\pi_k} \rangle\]and store the result as the action that will be selected by $\pi_{k+1}$. Since we agreed that all these policies will be deterministic, we may remove a bit of the storage redundancy, if we allow the algorithm just to store the action chosen by $\pi_{k+1}$ at every state (and eventually produce the output in this form), rather than requiring it to produce a probability vector for each state, which would have a lot of redundant zero entries in it. Correspondingly, we will further abuse notation and will allow deterministic memoryless policies to be identified with $\mathcal{S} \to \mathcal{A}$ maps. Thus, $\pi_{k+1}: \mathcal{S} \to \mathcal{A}$.

Given $v^{\pi_k}$, a vector of length $\mathrm{S}$, the cost of evaluating the argument of the maximum is $O(\mathrm{S})$. Thus, the cost of computing the maximum is $O(\mathrm{S}\mathrm{A})$: This is where the number of actions appears (in these steps) in the runtime.

Our main result will be a theorem that states that after $\tilde O( \mathrm{SA}/(1-\gamma))$ iterations, the policy computed by policy iteration is necessarily optimal (and not only approximately optimal!). The proof of this result hinges up on two key observations:

- Policy iteration converges geometrically

- After every $H_{\gamma,1}$ iterations, it eliminates at least one suboptimal action at some state.

The first result follows from comparing policy iteration with value iteration. We know that value iteration converges at a geometric rate regardless of its initialization. Hence, if we can prove that \(\| v^{\pi_k}-v^* \|_\infty \le \| T^k v^{\pi_0}-v^* \|_\infty\) then we will be done. In the so-called “policy improvement lemma”, we will in fact prove a result that implies

\[\begin{align} T^k v^{\pi_0} \le v^{\pi_{k}}\,, \qquad k=0,1,2,\dots\, \label{eq:pilk} \end{align}\]which is stronger than the geometric convergence result.

Lemma (Geometric Progress Lemma): Let $\pi,\pi’$ be memoryless policies such that $\pi’$ is greedy w.r.t. $v^\pi$. Then,

\[\begin{align*} v^\pi \le T v^{\pi} \le v^{\pi'}\,. \end{align*}\]Proof: By definition, $T v^\pi = T_{\pi’} v^\pi$. We also have $v^\pi = T_\pi v^\pi \le T v^\pi$. Chaining these, we get

\[\begin{align} v^\pi \le T v^{\pi} = T_{\pi'} v^{\pi}\,. \label{eq:pilemmabase} \end{align}\]We prove by induction on $i\ge 1$ that

\[\begin{align} v^\pi \le T v^{\pi} \le T_{\pi'}^i v^{\pi}\,. \label{eq:pilemmainduction} \end{align}\]From this, the result will follow by taking $i\to \infty$ of both sides.

The base case of induction $i=1$ has just been established. For the general case, assume that the required inequality holds for $i\ge 1$. We show that it also holds for $i+1$. For this, apply $T_{\pi’}$ on both sides of Eq. \(\eqref{eq:pilemmainduction}\). Since $T_{\pi’}$ is monotone, we get

\[\begin{align*} T_{\pi'} v^\pi \le T_{\pi'}^{i+1} v^{\pi}\,. \end{align*}\]Chaining this with Eq. \(\eqref{eq:pilemmabase}\), we get

\[\begin{align*} v^\pi \le T v^\pi = T_{\pi'} v^\pi \le T_{\pi'}^{i+1} v^{\pi}\,, \end{align*}\]finishing the inductive step, and hence the proof. \(\qquad \blacksquare\)

The lemma shows that the value functions are monotonically increasing. Applying this lemma $k$ times starting with $\pi = \pi_0$ gives Eq. \(\eqref{eq:pilk}\) and this implies the promised result:

Corollary (Geometric convergence): Let \(\{\pi_k\}_{k\ge 0}\) be the sequence of policies produced by policy iteration. Then, for any \(k\ge 0\),

\[\begin{align} \|v^{\pi_k} - v^*\|_\infty \leq \gamma^k \|v^{\pi_0} - v^*\|_\infty\,. \label{eq:pig} \end{align}\]Proof: By \(\eqref{eq:pilk}\),

\[T^k v^{\pi_0} \le v^{\pi_k} \le v^*\,, \qquad k=0,1,2,\dots\,.\]Hence,

\[v^* - v^{\pi_k} \le v^* - T^k v^{\pi_0}\,, \qquad k=0,1,2,\dots\,.\]Taking componentwise absolute values and then the maximum over the states, we get that

\[\|v^* - v^{\pi_k}\|_\infty \le \|v^* - T^k v^{\pi_0}\|_\infty = \|T^k v^* - T^k v^{\pi_0}\|_\infty \le \gamma^k \|v^* - v^{\pi_0}\|_\infty\,,\]which is the desired statement. In the equality above we used the Fundamental Theorem and in the last inequality we used that $T$ is a $\gamma$-contraction. \(\qquad\blacksquare\)

We now set out to finish by showing the “strict progress lemma”. The lemma uses the corollary we just obtained, but it will also require some truly novel ideas.

Lemma (Strict progress lemma): Fix an arbitrary suboptimal memoryless policy $\pi_0$ and let \(\{\pi_k\}_{k\ge 0}\) be the sequence of policies produced by policy iteration. Then, there exists a state $s_0\in \mathcal{S}$ such that for any $k\ge k^*:= \lceil H_{\gamma,1} \rceil +1$,

\[\pi_k(s_0)\ne \pi_0(s_0)\,.\]The lemma shows that after every \(k^* = \tilde O \left( \frac{1}{1-\gamma}\right)\) iterations, policy iteration eliminates one action-choice at one state until there remains no suboptimal action to be eliminated. This can only be continued for at most $SA - S$ times: In every state, at least one action must be optimal. As an immediate corollary of the progress lemma, we get the main result of this lecture:

Theorem (Runtime Bound for Policy Iteration): Consider a finite, discounted MDP with rewards in $[0,1]$. Let \(k^*\) be as in the progress lemma, \(\{\pi_k\}_{k\ge 0}\) the sequence of policies obtained by policy iteration starting from an arbitrary initial policy $\pi_0$. Then, after at most \(k= k^* (\mathrm{S}\mathrm{A}-\mathrm{S}) = \tilde O\left( \frac{\mathrm{S}\mathrm{A}-\mathrm{S} }{1-\gamma } \right)\) iterations, the policy $\pi_k$ produced by policy iteration is optimal: $v^{\pi_k}=v^*$. In particular, policy iteration computes an optimal policy with at most \(\tilde O\left( \frac{ \mathrm{S}^4 \mathrm{A} +\mathrm{S}^3{\mathrm{A}^2} }{1-\gamma} \right)\) arithmetic and logic operations.

It remains to prove the progress lemma. We start with an identity which will be useful beyond the proof of this lemma. The identity is called the value difference identity and it gives us an alternate form of the difference of values functions of two memoryless policies. Let $\pi,\pi’$ be two memoryless policies. Recalling that $v^{\pi’} = (I-\gamma P_{\pi’})^{-1} r_{\pi’}$, by algebra, we find that

\[\begin{align*} v^{\pi'} - v^{\pi} & = (I-\gamma P_{\pi'})^{-1} [ r_{\pi'} - (I-\gamma P_{\pi'}) v^\pi] \\ & = (I-\gamma P_{\pi'})^{-1} [ T_{\pi'} v^\pi - v^\pi]\,. \end{align*}\]Introducing

\[g(\pi',\pi) = T_{\pi'} v^\pi - v^\pi\,,\]which we can think of the “advantage” of $\pi’$ relative to $\pi$, we get the following lemma:

Lemma (Value Difference Identity): For all memoryless policies \(\pi, \pi'\),

\[v^{\pi'} - v^\pi = (I - \gamma P_{\pi'})^{-1} g(\pi',\pi)\,.\]Of course, a symmetric relationship also holds.

With this, we are now ready to prove the progress lemma. Note that if \(\pi^*\) is an optimal memoryless policy then for any other memoryless policy $\pi$, \(g(\pi,\pi^*)\le 0\). In fact, the reverse statement also holds: if the above holds for any $\pi$, $\pi^*$ must be optimal. This makes it \(-g(\pi_k,\pi^*)\) an ideal target to track the progress that policy iteration makes. We expect this to start at a high value and decrease as $k$ increases. Note, in particular, that if

\[\begin{align} -g(\pi_k,\pi^*)(s_0)<-g(\pi_0,\pi^*)(s_0) \label{eq:strictprogress} \end{align}\]for some state $s_0\in \mathcal{S}$ then, by algebra,

\[r_{\pi_k(s_0)}(s_0) + \gamma \langle P_{\pi_k(s_0)} , v^* \rangle > r_{\pi_0(s_0)}(s_0) + \gamma \langle P_{\pi_0(s_0)} , v^* \rangle\]which means that $\pi_k(s_0)\ne \pi_0(s_0)$. Hence, the idea of the proof is to show that Eq. \(\eqref{eq:strictprogress}\) holds for any $k\ge k^*$.

Proof (of the progress lemma): Fix $k\ge 0$ and \(\pi_0\) such that \(\pi_0\) is not optimal. Let \(\pi^*\) be an arbitrary memoryless optimal policy. Then, for policy \(\pi_k\), by the value difference identity and since \(\pi^*\) is optimal,

\[- g(\pi_k,\pi^*) = (I - \gamma P_{\pi_k}) (v^* - v^{\pi_k}) = (v^* - v^{\pi_k}) - \gamma P_{\pi_k} (v^* - v^{\pi_k}) \leq v^* - v^{\pi_k}\,,\]where the last inequality follows because $P_{\pi_k}$ is stochastic and hence monotone and because \(v^* - v^{\pi_k}\ge 0\). Our goal is to relate the right-hand side to \(-g(\pi_0,\pi^*)\). Since Eq. \(\eqref{eq:pig}\) allows us to relate the right-hand side to \(v^*-v^{\pi_0}\), and the value difference identity then lets us bring in \(-g(\pi_0,\pi^*)\), preparing to use Eq. \(\eqref{eq:pig}\), we first take the max-norm of both sides of the above inequality, noting that this keeps the inequality by the definition of the max-norm. Then, as planned, we use Eq. \(\eqref{eq:pig}\) and the value difference identity to get

\[\begin{align} \|g(\pi_k,\pi^*)\|_\infty & \leq \|v^* - v^{\pi_k}\|_\infty \leq \gamma^k \|v^* - v^{\pi_0}\|_\infty = \gamma^k \|(I - \gamma P_{\pi_0})^{-1} (-g(\pi_0,\pi^*))\|_\infty \nonumber \\ & \leq \frac{\gamma^k}{1 - \gamma} \|g(\pi_0,\pi^*)\|_\infty\,, \label{eq:plmain} \end{align}\]where the last inequality follows by noting that \((I - \gamma P_{\pi_0})^{-1} = \sum_{i\ge 0} \gamma^i P_{\pi_0}^i\) and thus from the triangle inequality and because \(P_{\pi_0}\) is a max-norm non-expansion, \(\| (I - \gamma P_{\pi_0})^{-1} x \|_\infty \le \frac{1}{1-\gamma}\| x \|_\infty\) holds for any \(x\in \mathbb{R}^{\mathrm{S}}\).

Now, define $s_0\in \mathcal{S}$ to be the state that satisfies \(-g(\pi_0,\pi^*)(s_0) = \| g(\pi_0,\pi^*)(s_0)\|_\infty\). Since $\mathcal{S}$ is finite, this exists. Noting that \(0\le -g(\pi_k,\pi^*)(s_0)\le \| g(\pi_k,\pi^*)\|_\infty\), we get from Eq. \(\eqref{eq:plmain}\) that

\[-g(\pi_k,\pi^*)(s_0) \leq \|g(\pi_k,\pi^*)\|_\infty \leq \frac{\gamma^k}{1 - \gamma} (-g(\pi_0,\pi^*)(s_0)).\]Now when \(k\ge k^*\), \(\frac{\gamma^k}{1 - \gamma} < 1\). Since \(\pi_0 \neq \pi^*\), \(0<\|g(\pi_0,\pi^*)\|_\infty = -g(\pi_0,\pi^*)(s_0)\) and thus,

\[\begin{align*} -g(\pi_k,\pi^*)(s_0) \leq \frac{\gamma^k}{1 - \gamma} (-g(\pi_0,\pi^*)(s_0)) < -g(\pi_0,\pi^*)(s_0)\,, \end{align*}\]which is Eq. \(\eqref{eq:strictprogress}\), and thus, by our earlier discussion, \(\pi_k(s_0)\ne \pi_0(s_0)\). The proof is done because this holds for any \(k\ge k^*\). \(\qquad\blacksquare\)

Is Value Iteration Inferior?

Our earlier result on the runtime of value iteration involves a $\log(1/\delta)$ term which grows without bounds as $\delta$, the required precision level, decreases towards zero. However, at this stage it is not clear whether this extra term is the result of a loose analysis or whether it is a property of value-iteration.

Can value iteration be guaranteed to find an optimal policy with computation which is polynomial in $\mathrm{S}$, $\mathrm{A}$ and the planning horizon $1/(1-\gamma)$, assuming all value functions takes values in $[0,1/(1-\gamma)]$?

Calling any algorithm that achieves the above strongly polynomial, we see that with this terminology we can say that policy iteration is strongly polynomial. Note that in the above definition rather than assuming that the rewards lie in $[0,1]$, we use the assumption that the value functions for all policies take values in $[0,1/(1-\gamma)]$. This is a weaker assumption, but checking our proof for the runtime on policy iteration we see that it only needed this assumption.

However, as it turns out, value-iteration is not strongly polynomial:

Proposition: There exists a family of MDPs with deterministic transitions, three states, two actions and value functions for all policies taking values in $[0,1/(1-\gamma)]$ such that the worst-case iteration complexity of value iteration over this set of MDPs to find an optimal policy is infinite.

Here, iteration complexity means the smallest number of iterations $k$ after which $\pi_k$, as computed by value iteration, is optimal, for any of the MDPs in the family. Of course, an infinite iteration complexity also implies an infinite runtime complexity.

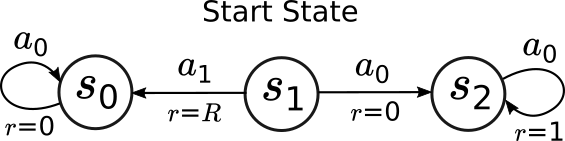

Proof: The MDP is depicted in the following figure:

The circles show the states with their names in the circles, the arrows with labels $a_0$ and $a_1$ show the transitions between the states as a result of using the actions. The label $r=\cdot$ shows how much reward is incurred along a transition. On the figure, $R$ is not a return, but a free parameter, which is chosen in the interval $[0,\gamma/(1-\gamma)]$ and which will govern the iteration complexity of value iteration.

We consider value iteration initialized at $v_0 = \boldsymbol{0}$. It is easy to see that the unique optimal action at $s_1$ is $a_0$, incurring a value of $\gamma/(1-\gamma)$ at this state. It is also easy to see that $\pi_0(s_1)=a_1\ne a_0$. We will show that value iteration can “hug” action $a_1$ at state $s_0$ indefinitely as $R$ approaches $\gamma/(1-\gamma)$ from below. For this, just note that $v_k(s_0)=0$ and that $v_k(s_2) =\frac{\gamma}{1-\gamma}(1-\gamma^k)$ for any $k\ge 0$. Then, a little calculation shows that $\pi_k(s_1)=a_1$ as long as $R>v_k(s_2)$. If we want value iteration to spend more than $k_0$ iterations, all we have to do is to choose $R = \frac{v^*(s_2)+v_{k_0}(s_2)}{2}<\gamma/(1-\gamma)$. \(\blacksquare\)

It is instructive to note how policy iteration avoids the blow-up of the iteration-counts. This result shows that value-iteration, as far as we are concerned with calculating an optimal policy, exactly, is clearly inferior to policy iteration. However, we also had our earlier positive result for value iteration that showed that the cost of achieving $\delta$-suboptimal policies is at most $\log(1/\delta)$ (and polynomial in the remaining quantities).

What does this all mean? Should we really care about that value-iteration is not finite for exact computation? We have many reasons to not to care much about exact calculations. In the end, we will do sampling, learning, all of which make exact calculations impossible. Also, recall that our models are just models: The models themselves introduce errors. Why would we want to care about exact optimality? In summary:

Exact optimality is nice to have, but approximate computations with runtime growing mildly with the required precision should be almost equally acceptable.

Yet, it remains intriguing to think of how policy iteration can just “snap” into the right solution and how by changing just a few lines of code, a drastic improvement in runtime may be possible. We will keep returning to the question of whether an algorithm has some provable advantage over some others. When this can be shown, it is a true win: We do not need to bother with the inferior algorithm anymore. While this is great, remember that all this depends on how the problems are defined. As we have seen before, and we will see many more times, changing the problem definition can drastically change the landscape of what works and what does not work. And who knows, some algorithm may be inferior in some context, and be superior in some other.

Notes

The runtime bound on policy iteration

The first result that showed that after $\text{poly}(\mathrm{S},\mathrm{A},\frac{1}{1-\gamma})$ arithmetic and logic operations one can compute an optimal policy is due to Yinyu Ye (2011). This was a real breakthrough of the time. The theorem we proved is by Bruno Scherrer (2016) and we followed closely his proof. This proof is much simpler than the first one by Yinyu Ye, though the main ideas can be traced back to the proof of Yinyu Ye.

Runtime of value iteration

The example that shows that value iteration is not strongly polynomial is due to Eugene A. Feinberg, Jefferson Huang and Bruno Scherrer (2014).

Ties and stopping

More often than one may imagine, two actions may tie for the maximum in the above problem. Which one to use in this case? As it turns out, it matters only if we want to build a stopping condition for the algorithm that stops the first time it detects that $\pi_{k+1}=\pi_k$. This stopping condition takes $O(\mathrm{S})$ operations, so is quite cheap. If we use this stopping condition, we better make sure that when there are ties, the algorithm resolves them in a systematic fashion, meaning that it has a fixed preference relation over the actions that it respects in case of ties. Otherwise, in the case when there are two optimal actions at some state $s$, $\pi_k$ is an optimal policy, $\pi_{k+1}$ may choose the optimal action that $\pi_k$ did not choose, and then $\pi_{k+2}$ could choose the same action as $\pi_k$ at the same state, etc. and the stopping condition would fail to detect that all these policies are optimal.

Alternatively to resolving ties systematically one may simply change the stopping condition to checking whether $v^{\pi_k} = v^{\pi_{k+1}}$. The reader is invited to check that this would work. “In practice”, though, this may be problematic if $v^{\pi_k}$ and $v^{\pi_{k+1}}$ are computed with finite precision and somehow the approximation errors that arise in this calculation lead to different answers. Can this happen at all? It can! We may have $v^{\pi_k} = v^{\pi_{k+1}}$ (with infinite precision), while $r_{\pi_k}\ne r_{\pi_{k+1}}$ and $I-\gamma P_{\pi_k} \ne I-\gamma P_{\pi_{k+1}}$. And so with finite precision calculations, there is no guarantee that we get the same outcomes in the two cases! The only guarantee that we get with finite precision calculations is that with identical inputs, the outputs are identical.

An easy way out, of course, is just to use the theorem above and stop after the number of iterations is sufficiently large. However, this may be needlessly, wasteful.

References

- Feinberg, E. A., Huang, J., & Scherrer, B. (2014). Modified policy iteration algorithms are not strongly polynomial for discounted dynamic programming. Operations Research Letters, 42(6-7), 429-431. [link]

- Scherrer, B. (2016). Improved and generalized upper bounds on the complexity of policy iteration. Mathematics of Operations Research, 41(3), 758-774. [link]

- Ye, Y. (2011). The simplex and policy-iteration methods are strongly polynomial for the Markov decision problem with a fixed discount rate. Mathematics of Operations Research, 36(4), 593-603. [link]